SUNDAY, 17 NOVEMBER 2019

Sometimes you become interested in something, and then, once you start learning more about it, you lose interest. The Vietnam War (1955-1975, or more specifically 1962-1973) is not such a historical theme. My interest in the war was initially aroused by the 1982 Sylvester Stallone movie, First Blood, about the veteran struggling with the local authorities in a small town in America. The main character, John Rambo, experiences flashbacks of his time in Southeast Asia. He remembers booby traps and ambushes in the dense jungles of Vietnam, as he tries to survive in a similar environment outside a fictional town in Washington state.

In time, information drifted into my teenage brain that America – the strongest military power in the world – had lost the war in Vietnam – a country of mostly poor peasants.

My interest was aroused, to say the least.

By the mid-eighties, there was the Oliver Stone movie, Platoon – which I didn’t quite understand, other than that everything was messed up and that the Americans couldn’t work out what went wrong. A few years later, the series, Tour of Duty, showed on South African television translated into Afrikaans as Sending Viëtnam (Mission Vietnam), with as theme song the ominous Rolling Stones number, “Paint It Black”.

For me as a teenager, with music from the era with which I identified more easily than with 1940s music, the Vietnam War felt closer than the more well-known World War II we learned about in school. Add to that the mystery of the American defeat, with half of America supporting the war, and the other half marching furiously through the streets, and later even veterans of the war growing their hair and beards and protesting against the war, and it’s no surprise that the Vietnam story became a glowing lamp for the moth of my interest.

Although the old Saigon, now known as Ho Chi Minh City, is only a three-hour flight from where we live in southern Taiwan, I never strongly considered going there until recently. Maybe I reckoned that post-war Vietnam with its billboards advertising Coca-Cola and with commercial districts filled with modern office buildings would be somewhat of a disappointment to the serious student of History.

Nevertheless, by mid-2019 we decided the time had come, and by August our tickets had been booked.

* * *

I have read quite a bit about John F. Kennedy and the war, and Lyndon Johnson and the war. I read about the background of the war including the French colonial period; the period during World War II when Japan finally took control, and then withdrew; the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union; the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. I read about Ho Chi-Minh and the quest for national liberation, and about the legendary victory Vietnamese nationalists achieved over the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. I read about the Diem regime, about Buddhist protests against the South Vietnamese government, about the monk who set himself on fire in the middle of a busy intersection in Saigon in 1963, and about the Dragon Lady who said if more monks wanted to set themselves on fire, she would gladly provide the matches. And I read about Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon in the last years of American engagement, when everyone already knew that America had made a colossal mistake to get involved in Vietnam (and that it was, to put it simply, a monumental fuck-up).

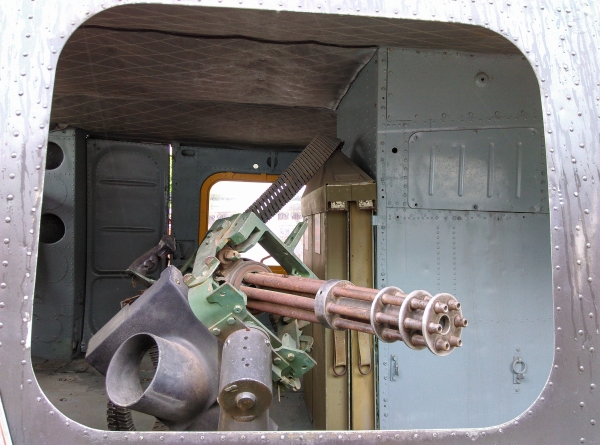

Having said that, my interest was always more audio-visual than academic: Images of rice paddies with peasants in conical hats bent over in the hot sun; American soldiers walking in a line on the wall of a rice paddy, machine guns ready for any incident; huts with thatched roofs in small hamlets set on fire by an American soldier; soldiers with panicked faces in a jungle; the Vietcong in black pyjamas flashing through the dense vegetation, only to disappear seconds later into a tunnel network; helicopters flying nose forward over rice fields and jungles, with a gaping open door, and a soldier leaning on a machine gun. And then of course the music from the mid to late sixties, and the early seventies.

* * *

On Sunday, 10 November 2019, I enjoyed my usual breakfast in our apartment in Kaohsiung, southern Taiwan, like any other morning. By Sunday night, N. and I were in Ho Chi Minh City. We arrived that afternoon at Tan Son Nhat International Airport, which at one point was one of the busiest military bases in the world.

The process of going through immigration and customs was more laboured than one might be used to. We had to download a form from a webpage two weeks before our departure, fill it in and email it back – on which we received another letter showing our names with our passport numbers along with the names of two or three dozen other people who would also go through immigration that day. After landing, we had to hand this letter – which we had to print out – with our passports and twenty US dollars cash to someone behind a counter. Our names were called after fifteen minutes, and then we were allowed to join the long queue to get stamps in our passports.

After immigration we got SIM cards (very easy, and cheap), and walked straight to a bus stop where the correct number bus happened to be waiting. And we were on our way – through busy streets full of motorcycles and scooters and taxis and buses and brightly-lit shops. More or less in the vicinity of our lodgings, we wandered through the streets for about fifteen minutes, and after finding our hotel in a colourful alley, we enjoyed our first dinner.

Monday morning we hit the streets. First stop was the War Remnants Museum – where tanks, aircraft and helicopters abandoned by the Americans on their withdrawal in 1973 are on display. The museum also has numerous items and photographs of the cost of the war – not just in material terms, but the terrible costs paid by ordinary men, women and children.

Next stop was the Independence Palace, built in 1963 at the behest of the then South Vietnamese president, Ngo Dinh Diem, after the previous building that served as presidential residence was partially destroyed by two bombs intended to get rid of him.

The palace is a time capsule – furniture and carpets from the 1960s and 1970s, maps on the walls of war rooms where generals and politicians discussed strategy, books in the library, telephones and other communications devices that gather dust in rooms in the basement that served as a bomb shelter.

There’s even a helicopter on the roof at the back of the building that still seems to be waiting to transport the last president of South Vietnam to safety. That the helicopter is still on the roof is a testament to the fact that the last president, Duong Van Minh, the third president in ten days and in the hot seat for only two days, refused to flee, even when North Vietnamese tanks and troops finally burst through the gates on 30 April 1975.

To round off the visit, we viewed a separate exhibit on prominent Vietnam leaders over the past 150 years or so, and then went to take photos at two tanks parked near the gates that were so unceremoniously flattened in April ’75.

The next day was gentler on the mind: the old Saigon Central Post Office, inaugurated in 1891, and the Notre Dame Cathedral, about ten years older than the post office.

Then it was the turn of the Gia Long Palace – now the Ho Chi Minh City Museum. The palace was built in the late 1880s to serve as a museum, but for decades had been used as an official residence by various civil servants.

The exhibits were interesting enough, but my interest was more the events of late 1963. On 1 November of that year, a group of South Vietnamese generals launched a coup against the government of Ngo Dinh Diem. Diem and his younger brother and main advisor, Ngo Dinh Nhu, their older brother, Ngo Dinh Thuc, and other relatives had lived in the Gia Long Palace since Diem ordered the Presidential Palace (the old colonial governor’s residence) to be demolished and rebuilt in 1962. By late afternoon of November 1st, the brothers were aware of developments, and escaped the palace through a secret tunnel.

After the palace, we checked in at the Saigon Metropolitan Opera House (dating back to 1897), stopped for beer and sandwiches, and then walked the two kilometres or so to the Vietnam History Museum via Google Maps instructions.

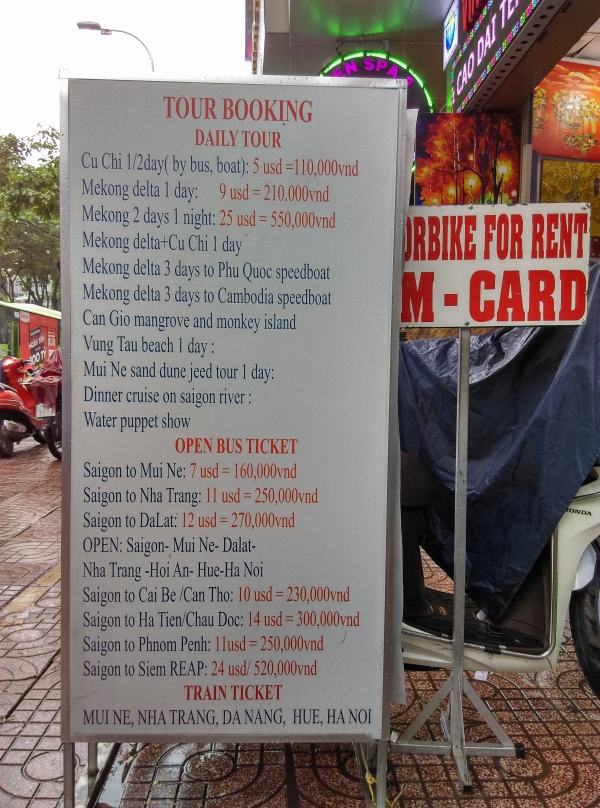

On Wednesday we were up early to join the two-hour tour to the Cu Chi Tunnels – part of an extensive network of tunnels used between the fifties and the seventies to smuggle weapons, troops, food and other supplies into South Vietnam. As it befits a tourist attraction, there were refreshments and souvenirs for sale.

For me this was quite an important experience: after so many films and TV shows about the war to stand in a real piece of Vietnamese jungle.

For a price you could also play soldier and pull the trigger a few times on one of the weapons used during the conflict: R40 ($2.60) per bullet for M16 and AK47; somewhat cheaper for other weapons.

After going for a light lunch back in Ho Chi Min at the Ben Thanh Market, it was time for a bit of a pilgrimage for me. I had been fascinated for some time by the act of protest of the Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, who set himself on fire at a busy intersection in the then Saigon on 11 June 1963. For years, there had been strife between the Diem government and the Buddhist majority population, and Duc’s self-sacrifice made front page news worldwide. I had been under the impression that the incident occurred in the city of Hue (that’s where his blue car is still kept), so when I read the previous night in my Wikipedia research that it did indeed take place in Saigon, I knew I had to see the intersection for myself. As it happened, the intersection was only about ten blocks straight down the road from our hotel.

That night we strolled around the commercial district and walked past the Rex Hotel – another iconic war-era building. The first guests, 400 US troops, signed in in 1961. They were the first company-strength soldiers to arrive in Vietnam, and stayed in the Rex for a week until their camp was ready. The hotel was also where the US military leaders held their daily press conference during the war. And the rooftop bar was where military officials and war correspondents hung out every night. In 1976, it was also at this hotel where the reunification of Vietnam was announced.

On Thursday, I dragged my travel companion to another place of importance only to people with a somewhat extreme interest in either the former South Vietnam or the Vietnam War, or both.

As mentioned earlier, the two Ngo brothers were aware of a coup attempt against their rule in November 1963. After escaping through a secret tunnel, they were taken to the Chinese business district in Saigon. They spent a few hours at an ally’s house, then went to the St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church. Here they sat at the back of the church while an early service was underway. Shortly afterwards, they were recognised in the courtyard of the church, and by 10:00 in the morning an armoured personnel carrier with two jeeps stopped in front of the church. The two brothers were arrested. The plan was to take them to military headquarters, but when the convoy stopped at a railroad crossing, the bodyguard of one of the coup leaders first killed one brother, and then the other in the back of the vehicle (it is still not clear exactly what happened and why).

Seeing that I was knee-deep in sixties politics and South Vietnam and the war by this time, it made sense to pay a visit to the church where the brothers spent their last moments before their downfall.

After the church, we walked a few blocks to a Tao temple.

Then we returned to modern Ho Chi Minh where we enjoyed lunch in the Bitexco Financial Tower.

After lunch we took the elevator to the viewing deck.

Our last attraction for the day was the Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts. The main building was constructed between 1929 and 1934 as a residence for the Hua family. The museum moved to the premises in 1987. There are several rooms with beautiful and interesting works of art, but what attracted my attention most were the architecture, the rooms themselves, and things like the staircases, the shutters and the stained glass windows.

Friday morning we were on the sidewalk early to take a bus back to the airport. Like when we arrived, the bus was on time and very comfortable. At the airport we had to stand in another long, winding cue. We rewarded ourselves with a pleasant breakfast in the Duty Free section. About an hour after our designated departure time, a bus dropped us of at an airplane with a photo of a Vietnamese woman with a bottle of Coca-Cola in the hand. Strange concrete structures on the edge of the runway were a last reminder that this piece of land and the country itself were just a few decades removed from one of the most brutal conflicts of the twentieth century.

Two hours after we landed, I was already back in a class in Taiwan. And Saturday morning it was breakfast again at home – like any regular weekend.

To view more photos, please visit my Flickr albums:

Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts

______________________