Week 17, 2020

MONDAY, 20 APRIL 2020

This week sees a new project: A weekly piece on my two journal sites (this one and BrandSmit.NET).

I plan to add something every day – hopefully interesting or useful, or perhaps educational.

By the end of this week, my regular readers (there must be one or two; surely not all my readers are bots from Ukraine or Russia) would either have something new to enjoy, or I’ll quietly change this post to “Draft” or “Under review” and delete it completely after a few weeks.

That’s it for now, seeing that it’s already Tuesday morning, at 43 minutes past midnight.

TUESDAY, 21 APRIL 2020

What drove me to do this (I’m already asking on just the second day of my project)? Here I sit and type falsely that it’s still Tuesday, 21 April whilst the silence in the alley confirms what the clock in the right corner of my computer screen is saying: That it is already Wednesday, and already almost a good quarter past one … and I was already half asleep hours ago on the train on my way home.

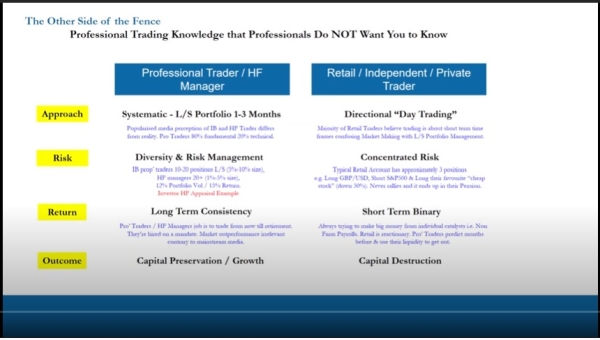

In these weekly “newsletters” I also plan to play curator and mention good content I discover in other corners of the Internet between Monday morning and Sunday night. One or two snippets of text on Twitter have caught my attention, but the most useful video I’ve watched so far was one of just over two hours – a lecture by a former Goldman Sachs trader about the pitfalls in which ninety percent of people trying to make money from home by trading on the financial and stock markets fall every day. Very interesting. Still have to finish watching it – the mountain of vegetables I call my dinner wasn’t massive enough last night that I could finish watching the entire video in one sitting.

Anyway, I’m practically lying with my face on the keyboard, so I’m done for now.

WEDNESDAY, 22 APRIL 2020

Before I started looking into trading on Forex and other markets, I had spent some years learning sports betting – waging money in calculated risks, aiming for a slight profit margin.

My way of trading is similar to sports betting in that I use small stakes, with limited exposure. I don’t buy and hold shares before I sell them. I enter buy or sell contracts before exiting the trade after some period of time (could be thirty minutes later, or two weeks later). I wage money on a calculated risk that a particular price is going to go up or down, based on certain criteria. I don’t know that a price is going to go up or down, and I don’t predict that it will do this or that. Because I don’t predict, and I don’t make public any opinion, I won’t feel embarrassed if it goes the wrong way. I won’t feel like a fool for making a certain prediction. I therefore won’t feel like the market “owes” me something, or that I need to get back at it for taking something from me.

I understand that I take calculated risks. I know before I enter a trade what the maximum risk is that I am willing to take. In some cases I also know where I would likely be getting out.

Is this what professional traders do at hedge funds and investment banks? Not sure. I’ve never sat down with one for a chat. I am definitely curious to know what they do and how they manage their portfolios. Maybe after watching more videos like the one about Anton Kreil “annihilating” retail brokers and “trading educators”, I might change how I trade. He does strike one as the proverbial “real deal”, and I am certainly always open to learning and improving what I do.

So, here’s a link to what I already predict would be my video of the week (it was either this or an animated video about how long people stayed alive after being guillotined). It is a seminar by the aforementioned Anton Kreil, of the Institute of Trading and Portfolio Management:

It’s slightly over two hours long, so I suggest, if you are interested in this, to make some time to watch it with the attention it deserves.

THURSDAY, 23 APRIL 2020

13:04

This morning, as I was making breakfast, I had a passing thought about how N. and I need to renew our passports within the next two years. Then I thought about Taiwanese citizenship. Next thought was about one of the requirements a foreigner has to fulfill before they can apply for Taiwanese citizenship, namely to have a Chinese name.

The way one decides on a name is usually to go through Chinese words and surnames, and then to choose a three-character combination that sounds okay, with a meaning when thrown together that wouldn’t cause a bank clerk or a traffic cop to burst out laughing when you tell them your local name.

Now, I have played around with one or two names over the years – I’ve been both a Mr. Chen and a Mr. Bu. The latter was derived from the name most people call me, “Brand”, which is pronounced in Chinese as “Bu-lan-de”.

Nevertheless, this morning I thought of coming up with a name that would derive from my first baptismal name: Barend.

After reviewing the Far East 3000 Chinese Character Dictionary, I provisionally decided on …

Fairly easy to write; the “Ba” is actually an obscure Chinese surname, and “Ren-de” means something along the lines of charity or goodwill.

A quick Google search provided three examples of these three characters as a name. One is of a village in the Netherlands named, Barendrecht. The second case is of a man named “Barende” who did not want to listen to his grandfather, and the third reference translates loosely as follows: “When I came to Barende’s house again, his family was waiting there, and several monks were chanting. Seeing me coming, his family’s eyes were full of hostility. Angry, they also punched my child.”

So, that’s it, for now. I first have to introduce myself as “Mr. Ba ” to a few people in public. If they don’t burst out laughing hysterically – or worse, I’ll know I have a winner.

14:18

By the way, whilst taking in my daily dose of numbers and opinion on the virus this morning, I was reminded of the childhood rhyme, “Ring-a-ring-a-roses”. I thought again how interesting it was that the rhyme, according to tradition, had been transmitted from one generation to the next for almost 700 years – since the Black Death in the fourteenth century.

Seconds later, I was on Wikipedia, where I was informed that the medieval origins were, according to experts, probably nonsense.

Several reasons are raised against the notion that the rhyme dates back to the fourteenth, or the seventeenth century, including that the story about its earlier origins only started making the rounds after World War II, that the symptoms described in the rhyme – such as the ring on the skin – apparently don’t correspond with those of the Plague, and that European and nineteenth-century versions of the rhyme suggest that the “fall” in the last line was not a literal fall, but a curtsy or a bow, which was common in other dramatic singing games.

And so another old belief bites the dust.

FRIDAY, 24 APRIL 2020

Latest episode of the recurring dream (“On time, but I couldn’t prove who I was”; “Managing to get my stuff together”): I am once again in a house in South Africa, preparing to return to Taiwan the next day. I look around the room: too many suitcases standing around; too many containers that need to be filled (or that can be filled). Another problem is with my clothes. I’ve just washed it, so it’s not dry yet. I also remember that I haven’t bought “South African groceries” yet, and time is running low.

Then there’s the young guy who shows me his portfolio of designs. I look at it politely, and make positive comments, but he shows a lack of respect by putting his feet on the table as I look at his work. I think to myself, in the dream, “What’s the point anyway? The guy’s just going to get an office job.”

What does this all mean? I do have an idea though that the “wet laundry” refers to this new project of mine where I publish text for everyone to see before going through it a dozen times.

* * *

NEXT WEEK: My opinion on the virus, stay-at-home orders, and a list of articles and other pieces of content that have formed my opinion on the subject since February.

* * * * * * * * * * * *