Week 18, 2020

MONDAY, 27 APRIL 2020

Seeing that I’m still working on my coronavirus reading list, something more mundane …

I just got back from the supermarket. I left, on foot, about twenty minutes before ten. The sidewalks were scattered with people. Some people were trying on shoes in the shoe store, others were closing stores. On one corner people were throwing bags in the garbage truck. At the next corner, groups of people were gathered around tables inside and outside the Family Mart. Here and there a parent with a child in hand. At the next corner, at the fourth of ten east-west streets running to the coast in Kaohsiung, I turned left.

The supermarket was still busy. In the fruit section, I picked two apples for our breakfast tomorrow morning. At the dairy fridge, a woman politely asked me in English to get her two boxes of low-fat brown rice milk from a high shelf. Shortly after, I grabbed my usual bottle of drinking yogurt, and on my way to pay remembered that I also needed oatmeal.

At the checkpoint, the only client in front of me was a young man with tattoos on his arms and legs. He was chewing betel nut, and paid for his dozen beers with a fresh NT$1,000 note.

As usual, I paid for my goods with the correct change, and sauntered the twelve minutes home.

TUESDAY, 28 APRIL 2020

Eleven o’clock at night is TV and snack time in our household. TV these days mostly means Netflix. And because I have a pathological inability to make snappy choices, we watch series rather than films.

We started last year with a Canadian-American series on time traveling called, Travelers. Then we watched a German series, also about time travel, called Dark. We followed that up with all the seasons of Big Bang Theory. Then we watched a French series about a man who discovered that a container that someone had wrongly delivered to his home was a portal to his own past – also dark, but not as dark as the German series where people discovered a portal in a cave outside their town. We also recently watched the Austro-German series Freud. The late nineteenth-century historical and political background was of course highly interesting, but the history and the somewhat fictional doings of the young Doctor Freud are not everyone’s cup of tea.

The series we are currently working on is an early 2000s series about a mother and daughter in a small town in Connecticut.

Here’s the thing: I have feelings about the main character – the mother. She’s supposed to evoke sympathy as a single mother and strong female figure, but she becomes more annoying with almost every episode. (I’m talking about the character now, not the actress who does an excellent job portraying the character.) At first I thought it was just me who think there’s something wrong with the woman, but a journalist at the time described the character of Lorelai Gilmore as “narcissistic and at times emotionally unstable, with strains of sociopathy”. A writer on a popular website referred to her “intense, overwhelming self-absorption”, and also opined that she is rude to people but always requires special treatment. Then there are her relationships with men. She and the owner of a local restaurant clearly have a good connection, but she ignores this and rather embarks on a string of relationships with men about whom she is not nearly as serious as they are about her. She even gets engaged to the one guy. When it becomes clear that she just wants to try out what it feels like to be on the verge of getting hitched, she breaks up with him – a few days before the wedding. A year or so later she’s disappointed that he seems to have gotten over his broken heart too quickly. And she speaks incessantly; she’s frivolous, and incredibly selfish. She’s driving me nuts! The creators of the character deserve some serious credit. After all, they could have gone for an underdeveloped, but safer character.

Anyway, it’s time for my late night cup of tea, and another episode of Gilmore Girls.

WEDNESDAY, 29 APRIL 2020

Old readers will know that the bits of text I’ve been producing since last week are not my first literary endeavours. But for the five or six new readers who haven’t yet cast an eye on some older pieces, I decided to give a quick overview of the seven collections I made available for free in 2017 and 2018.

The first volume was In the grip of heretics – or, The Christian, a volume on religion, arguments against fundamentalism, and options for the unbeliever. Not a table, a dog or a pencil is about identity and other questions about human existence. Time doesn’t really fly is a collection of pieces on topics that couldn’t fill a bundle on their own. The real, or non-real purpose of our existence is, as the title suggests, about the potential why’s of our existence. In As long as you remain standing I try to convince the reader that it is better to remain standing, and if you stumble, to get up again. The title of the next volume, The necessary unpleasantness, exposes my feelings at one point about the need to make money. The adult life is about my modest efforts to survive the challenges most adults face. Bundle 8 – On writing and the writer is still in the pipeline, but almost ready.

As I mentioned, the bundles are available for free in PDF at Archive.ORG. In case you wanted a printed copy or wanted to read it on your Kindle, you can purchase it from Amazon.COM. There are one or two changes I still want to make, and the introductions still need work if I have to be honest, but they are nonetheless available as they are.

THURSDAY, 30 APRIL 2020

[Initially just a note to myself. I should have known the piece was going to become another round of public self-criticism.

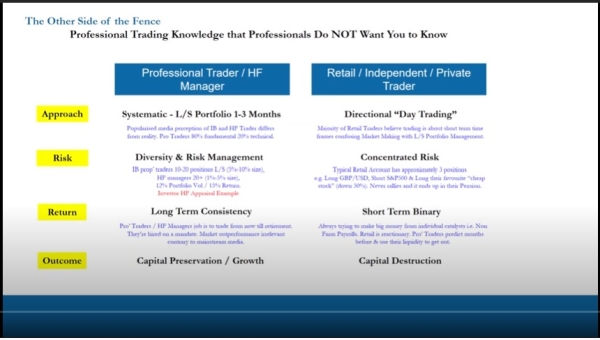

Quick explanation: Hundreds of thousands of people bet on a daily basis on horse racing in Britain. Betfair.com provides a platform where people place bets, but also where people can offer prices that are better than can be found at other bookmakers. This buying-and-selling of prices takes place quickly enough, especially in the last five to ten minutes before a race begins, and at large enough volumes – sometimes over a million dollars per race – that one can make money trading the prices, as in a stock market. This process is known as pre-race trading.]

Almost three years have passed, and to be honest, I still haven’t processed what went wrong with my once promising pre-race trading project.

By 2013, I was aware that over the previous few years I had failed to focus for long enough on one project to generate a stable income from it. I had been interested in making money from sports and statistics for some time, and had read about people like Paul Shires of TradeShark who discovered Betfair trading in 2008 and quit his job by 2010 to trade tennis full-time. At the beginning of 2014, I read Caan Berry’s PDF on pre-race trading, and although I wasn’t impressed with the quality of the manual, I thought pre-race trading looked like the type of project I wanted to focus on until I mastered it. You could start with nothing more than $200 in your account, and all the action took place over three hours during the UK afternoon – between 9pm and midnight in Taiwan.

And did I focus! Over the next two years, I spent hundreds of dollars on more training – videos, PDF tutorials, online seminars. I watched dozens of videos, and read enough on the topic to compile six documents with notes.

By mid-2017, I had lost steam, and shortly thereafter stopped completely. I did not say out loud that I was going to stop; I just knew I needed a break. Initially, the break was only a few days. After three weeks, I restarted the software and traded a few meetings. But the interest was gone. And the same problems resurfaced.

What then was the problem? The software (Geeks Toy) with which one trades pre-race was honestly outstanding. There was hardly a move or money-flow that wasn’t displayed in some way. You could see in several ways how the price was moving, where the price had been, where it was likely going, and what was going on in the other “markets” – that is, the other horses in the race.

As complex as it was – with every horse in the race actually forming its own market, but all the prices also integrating into one big market, namely the race, and as stupid as I had shown myself to be with numbers, I had managed to get a grip on most of it by the end of 2016. Why didn’t I make money with it?

Two reasons: I frequently failed to close my trades before the race began – which meant you suddenly found yourself in a totally different market, with prices jumping wildly, big gaps in prices, and the strong possibility that your entire account can be wiped out in seconds if you’re not careful. This problem was easy to identify. The real problem was that I was not successful enough in the five to ten minutes before the races started. As I again surveyed this morning the screenshots I took of some races, I once again realised that the problem was not that I didn’t understand what was going on. The problem was that I couldn’t get in often enough at a price at which I knew I needed to get in, and I couldn’t exit often enough at a price where I knew I had to get out. Speed was the problem. It was either my computer’s processing of the software, or my Internet connection, or my reaction. Whatever it was, I was too slow.

In a Word document in which I regularly made notes about my trading activity, I wrote the following on Thursday, 11 May 2017: “People think pre-race trading, especially scalping, is about horse racing, because of the ‘race’ part, or that it is about trading. What they often don’t realise before they’ve already spent a lot of money and a lot of time trying to master it and make some money is that it is in fact a video game. And if you’re not good at playing video games, especially fast ones where things change quickly, you will lose a lot of money, and waste a lot of precious time.”

FRIDAY, 1 MAY 2020

The first area of Kaohsiung where I lived when I arrived here in January 1999 was Fengshan – actually a city in her own right back then, but since 2010 a district. Fengshan is indeed much older than the city of which she is now a part. Kaohsiung was just a small fishing village until Japan took over the island in 1895, but Fengshan had already been an important administrative centre by the late eighteenth century.

On New Year’s Day we visited some historical places in my old district. In a former school for prospective government officials, now a museum known as Fongyi Academy, I came across a model of late eighteenth or early nineteenth-century Fengshan.

The first photo is of the whole town. Interesting to mention that the most important streets in modern Fengshan were laid out on the original dusty roads. The second photo shows where my first neighbourhood was – just across the river, on the outskirts of town.

For more photos of Taiwan, and other places, follow me on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/brandsmit.taiwan/

* * * * * * * * * * *

NEXT WEEK: The virus reading list … and other pieces of text.

* * * * * * * * * * *